Representatives from all over the world have spent most of the last month in Jamaica negotiating the future of deep-sea mining.

Based in Kingston, the International Seabed Authority, or ISA, is working on a set of rules to regulate the extraction of raw materials from the ocean floor. But despite weeks discussing the matter, many questions remain.

What is the current state of deep-sea mining?

By 2025, the ISA wants to define a set of legally binding rules to manage deep-sea mining — without these rules, any planned mining operation will not be able to get started. Discussions have been ongoing for several years, but these latest talks have laid bare the extent to which the new rules remain divisive, especially when it comes to the issues of underwater monitoring and avoiding environmental damage.

Several states, including Germany, Brazil and the Pacific island nation of Palau, have said they won't agree on the new rules until their environmental impact has been fully investigated. China, together with Norway, Japan and the microstate Nauru in the Central Pacific have pushed for a quick agreement so that mining companies can start putting their plans into action.

But that's looking increasingly unlikely. Of the 169 countries represented in the ISA, 32 are now in favor of suspending or even banning deep-sea mining outright, a stance supported by environmental organizations and many marine scientists.

Despite the concerns, however, the Canadian startup The Metals Company has already announced it plans to submit an application to the ISA for a commercial deep-sea mining operation in the coming months.

Who profits from deep-sea mining?

When it comes to deep-sea mining, the focus is primarily on manganese nodules and other minerals found on the ocean floor outside territorial waters. This is commonly called the high seas, and accounts for more than half of the world's oceans.

These areas are classified as the "common heritage of mankind," raw materials that belong to everyone, not one particular country. Managing and monitoring any potential mining activities in these regions would be the responsibility of the ISA, as outlined in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Many countries and corporations are interested in the commercial potential of deep-sea mining. The ISA has so far issued 31 exploration licenses for certain areas, five of which have gone to Chinese companies. But several other countries, including Germany, India and Russia, have also been exploring the seabed.

The UN's sea convention stipulates that any activities in the high seas must be equitably shared among states, and that would include profits from deep-sea mining. Critics like the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, however, remain skeptical of whether this would even be possible.

What kinds of metals can found in the ocean floor?

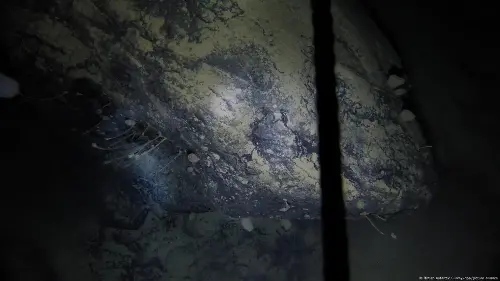

Mining companies are particularly interested in polymetallic nodules, also known as manganese nodules. These potato-sized lumps, which form over millions of years from sediment deposits, are composed mainly of manganese, cobalt, copper and nickel — raw materials which are a key component in electric car batteries. As the world makes the transition to renewable energy, the International Energy Agency expects the demand for these metals to double by 2040.

The ocean floor in what's known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone between Hawaii and Mexico holds vast amounts of manganese nodules. Mining companies aim to harvest these prized metals from a depth of between 4,000 to 6,000 meters (13,100-19,700 feet) with automated vacuum robots, bringing them to the surface with hoses.

Other areas in the Pacific, the Indian and the Atlantic Ocean also hold significant deposits of these minerals. In addition to manganese nodules, mining companies are also targeting polymetallic sulfides, which contain large amounts of copper, zinc, lead, iron, silver and gold, and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts, which are especially hard to break up and recover from the ocean depths.

How could deep-sea mining harm marine ecosystems?

Manganese nodules and mineral crusts aren't dead rocks — they're an important habitat for many sea creatures. According to marine scientists, more than 5,000 different species, some of which have barely been researched, make these unhospitable areas their home. At this depth, conditions are extreme: food is scare, sunlight is nonexistent, and the water pressure is 100 times higher than at sea level.

For that reason, the seabed ecosystem — and species that have adapted to living in these conditions — are extremely fragile. Mining robots, which vacuum up huge expanses in their search for manganese nodules, would destroy the ocean floor and suck up countless sea creatures. Even marine life found kilometers away from these mining areas would be disturbed by light and noise pollution as well as the far-reaching, swirling clouds of sediment. Fishing activity above the mining areas could be permanently disrupted.

To date, researchers have explored only around 1% of the deep sea area and its potential. A study released in July, for example, showed that the minerals present in manganese nodules are able to produce oxygen through electrolysis, in the complete absence of sunlight. Until now, scientists assumed that this only happened in nature through photosynthesis. Research is ongoing.

Marine scientists have warned that beginning deep-sea mining without sufficient knowledge of the potential consequences could be catastrophic for biodiversity and the as-yet little-known sea ecosystems. The necessary research could still take another 10 to 15 years, in part because the area is so difficult to reach.

Is deep-sea mining even worth it?

Countries like China are hoping for huge profits and a secure, independent source of raw materials, and expect to be mining for important minerals for decades to come. Mining companies have said deep-sea mining is less destructive than mining on land, and would eliminate many concerns of human rights abuses.

But a study from the German nonprofit Öko-Institut, commissioned by Greenpeace, has revealed that the raw materials found in manganese nodules aren't actually needed to fuel the energy transition, highlighting instead the development of new battery technologies like lithium-iron-phosphate accumulators.

Critics have also pointed out that mining companies have underestimated the costs and technical risks of commercial deep-sea mining. The technology has not yet been fully developed, and the extreme water pressure at such depths will make it difficult to repair robots and other mining equipment.

A growing number of major companies, including SAP, BMW, Volkswagen, Google and Samsung SDI have already pledged not to use any raw materials recovered from the seafloor, and have said they would not support mining activities. Several insurance companies, among them Swiss RE, have also ruled out underwriting such risky projects, which could also dent their profitability.

When could deep-sea mining begin?

So far, any potential mining areas have only been explored, not exploited. The Metals Company, however, has said it wants to apply for its first commercial mining license from the ISA by the end of 2024. Along with its subsidiary in Nauru, it plans to start operations in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in 2026. When, and if, the ISA will approve the license remains unclear.

Norway aims to start its own mining operation as soon as possible, in the North Atlantic between Greenland and the Svalbard archipelago, after getting the go-ahead from parliament in January. The 281,000-square-kilometer (108,570-square-mile) area, slighter smaller than Italy, is at a depth of 1,500 meters on the continental shelf. The ocean floor in this region belongs to Norway, meaning it's not controlled by the ISA. The country wants to start granting licenses for exploration next year, with mining operations planned for 2030.

However, environmental organization WWF has taken legal action against Norway's mining plans, with scientists warning of irreversible damage to the Arctic ecosystem and fisheries. Japan is also making plans to begin deep-sea mining operations in its underwater territory.

This article was originally published in German.