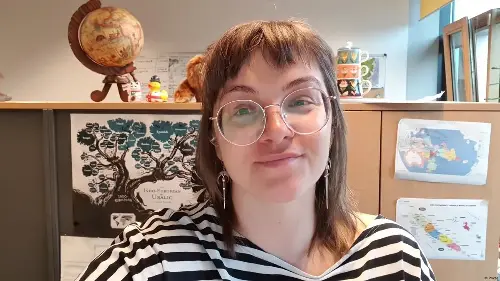

Hedvig Skirgard, a Swedish linguistics major who came to Leipzig for her postdoctoral studies, had only been in Germany for a few months when she needed to go to the doctor. The resulting experience still preoccupies her now, after several years of living and working in Germany.

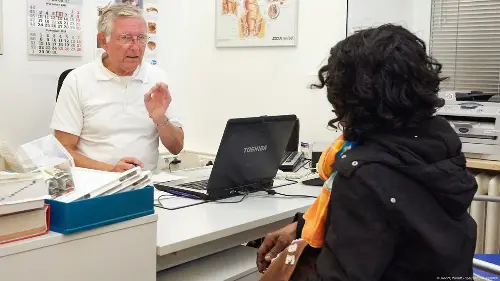

"My doctor recommended a few specialists," she said. "I contacted them using Google Translate and what little German I had acquired. I asked if they could speak English with me, but none of them could. I asked if there was any interpreting service available — there was not. One specialist suggested I'd bring a friend or a family member to interpret for me. This wasn't possible: I have no family here and no friend I felt comfortable bringing along to an intimate medical discussion."

The strangest thing, she remembers, was the impression she got that the doctors did not appear to know what to do when they don't share a language with their patients. "Could I be the first immigrant in my town to undergo a medical procedure without having advanced German-speaking skills? Surely not?"

Skirgard almost certainly wasn't. Germany's Federal Statistical Office found in 2023 that around 15% of people living in Germany do not primarily speak German at home. And yet, as Skirgard was a little bewildered to discover, there are few systems in place when health care providers meet non-German patients, and many doctors are not aware of what systems do exist. Eventually, Skirgard found a useful database of doctors who speak different languages — though her own doctor didn't know about it.

"It was stressful and scary, and I hope this doesn't happen to anyone else. I know of other cases that have gone less well," she said. "Doctors are feeling hassled and pressured to provide care outside of their comfort zone and capabilities."

Health care translation required in other countries

It appears the majority of German doctors would agree: in May, the German Medical Association's doctors' conference voted in favor of two motions demanding free professional interpretation services — on the grounds that the lack of such services was making it harder for them to do their jobs.

"Every day, we doctors treat patients whose mother tongue is not German," one of the motions read. "Often, communication is only possible with the help of family or colleagues from the medical profession, nursing staff or service personnel. This unprofessional language mediation is not only a burden for the translator, but also for the medical team and the patients, and it complicates the diagnosis or the appropriate treatment."

Such services aren't a new idea. In other European countries, it's up to the health care system, rather than the patient, to find a common language. In Skirgard's native Sweden, there is a centralized system in place that allows doctors to book a conference call with an interpreter if they have an appointment with a non-Swedish-speaking patient. In Norway, patients have a legal right to receive information about their health and medical treatment in a language they understand, while the Irish Health Service has issued guidelines on how doctors should find interpreters.

In Germany, meanwhile, doctors and patients are often left to muddle through as best they can — sometimes relying on charities and volunteers like the Leipzig-based Communication in Medical Settings, a university group based in Leipzig that organizes interpretations for doctors' appointments, mainly more refugees and asylum-seekers.

"We see ourselves as gap-filler for translation that should be done and paid professionally," Paulina, of Communication in Medical Settings, told DW, who preferred not to give her surname. "But we see that the gap is there, because neither the state or the health insurers or the doctors' offices or the hospitals will take responsibility for taking the costs."

'Nice to have' or 'need to have'?

As it happens, the coalition government of Chancellor Olaf Scholz is aware of the problem and promised in its 2021 coalition contract to make national state health insurers cover the cost of translation services. A spokesperson for the German Health Ministry confirmed to DW that this indeed was still part of the plan, and would recommend that the coalition parties introduce it to the Health Care Strengthening Act.

But that hasn't happened yet, and it seems it has been blocked by disagreements in the government coalition. Bernd Meyer, professor of intercultural communication at the University of Mainz, has been studied issues of language, integration and culture for many years, and co-wrote a book of recommendations on language in public institutions. He was invited to the Bundestag last year to explain why the measure is so necessary.

"Everyone says that this is a problem and that it needs to be solved," he told DW. "But there's a problem in the political implementation." Though he argues that providing such services would be relatively inexpensive, given the cost of the health care system overall, his understanding was that the coalition had, as Meyer put it, decided translation services were considered a "nice to have," rather than a "need to have."

"Basically it was blocked in the whole discussion about the budget and the debt brake," he said, referring to the mechanism that obliges the government to balance the books and places strict limits on new borrowing.

Germany is a multilingual society

As Skirgard and others have noted, Germany is trying to attract skilled labor. According to the German Economic Institute (IW), some 570,000 jobs could not be filled in 2023, and companies were struggling as a result. In September, Scholz signed a skilled labor agreement with Kenya to help bridge that gap.

Of course, some would say German is the official language and that anyone who lives here just has to learn it. "Oh, I agree, that's 100% true," said Skirgard. "But when someone arrives, month one from Kenya, and they break their bone, should they not get care until they take a German intensive course? I think if Germany wants to be a country that attracts skilled immigrants, then translation might be a 'need to have' and not a 'nice to have'."

Indeed, as researchers like Meyer often point out, the reality is that Germany is a multilingual society. Many people go through their lives rarely speaking German: during his research in a hospital, Meyer met a 60-year-old Portuguese heart attack patient with hardly any German skills who had spent over 30 years working in a German slaughterhouse.

"He basically carried halved pigs around all day, and in the evenings he went to a Portuguese social club and watched football," he said. "He just never had much contact with Germans. Why should he have? His life was OK. He never had a reason to learn German."

Though — being a linguist — Skirgard has learned German in her four years here, she also rarely uses it in her working life in the university where she works. "You can say that that's bad and shouldn't be that way, and I can fully understand that perspective," she said. "But that is the situation, so how do you deal with what's happening rather than what you want to happen?"

Edited by: Rina Goldenberg