He soars, feeling the warm updraft of air cushion his outstretched wings, which stretch 7 ft from tip to tip, as he flies towards the sun. In his youthful ebullience, he goes farther than before, further than he should. Too late, he realises this, as he feels the heat of the sun singe his feathers.

This is not the cautionary tale of Icarus. This is an Indian tale, and the moral is different.

Sampati sees his younger brother falter. Ever cautious, he shouts at him to slow down, turn around, but his brother won’t listen. Finally, with a powerful sweep of his wings, the great vulture surges ahead and shelters his brother under his wings. He feels the heat of the sun burn his feathers and tumbles towards Earth, wingless, powerless, comforted only by the thought that he saved his brother.

Sampati is a demigod, a vulture said to have been born not too far from where we stood, staring at a majestic cliff face in the Panna Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh.

Vultures rank amongst the world’s largest flying birds. With a wingspan longer than a tall man, they scour the skies, often flying over 100 km in a day, searching for food. Nature’s cleaning service, these scavengers can strip a carcass to the bone in hours. In India’s Swachh Bharat campaign, they have not received their due credit. We always seem to undervalue Nature’s services, don’t we?

Sadly, India’s vulture population has fallen from 40 million to about 30,000 over the past 30 years; the result of a vulture version of an opioid epidemic.

Diclofenac, introduced in 1973, has become one of the world’s most widely prescribed non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); a painkiller of choice, if you will. Generic versions entered the market in 1993, and veterinary versions entered India soon after. Farmers started administering it to ageing cattle to ease their pain. When those animals died, the drug lingered, and made its way into the vultures that fed on their carcasses.

The Gyps vultures common in India lack, or have only weak versions of, the enzyme machinery other animals use to break down diclofenac, making even tiny doses fatal. The drug swiftly damages their kidneys and, as uric acid levels climb, the bird’s organs become coated in white, toothpaste-like deposits. Death follows soon after.

Even low concentrations of the drug can overwhelm the vulture’s body. And because they are social feeders and congregate over a single carcass, a single tainted carcass can claim many birds. This is tragic irony at its finest: a scavenger done in because of a collapse of its body’s waste-management system.

***

It’s strange to think of something so innocuous decimating an entire species.

The “novel entities” boundary, within the Planetary Boundary framework developed by Johann Rockstrom, warns against the uncontrolled release of synthetic chemicals, plastics, and engineered materials that Earth systems cannot safely handle. The vulture is the canary in that coal mine.

I now look at the Voveran gel on my bedside table with fresh guilt.

Vibhu Prakash, former deputy director of the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), was among the first to notice that India’s vultures were vanishing in the wild. In the 1980s, as a young researcher at Keoladeo National Park, he saw thousands; when he returned in the 1990s, they had all but disappeared. Those that remained perched with drooping necks, lingering a few days before falling dead.

Food was not the issue. “In fact, when cattle died, people would leave them nearby because vultures cleared them quickly,” he says. “Now, carcasses took days to be eaten.”

Nesting sites were also available. None of the tissue samples tested had a pesticide load high enough to cause breeding failure or death. Nothing explained the collapse he was seeing. Given that fish- and bird-eating raptors appeared unaffected, pesticides didn’t seem to be the cause.

Could it be something in the carcasses?

Shortly thereafter, scientists found vultures in Pakistan dying the same way, and found diclofenac residue in their tissues. They then fed diclofenac-laced buffalo meat to captive birds to test their hypothesis; the vultures died. Prakash’s team tested tissue samples across India: three-quarters of the dead vultures had visceral gout, and all those samples contained diclofenac. They published their findings in 2004.

There was no doubt: Diclofenac was killing vultures. Prakash knew a ban on it would only work if there was a safe alternative. After extensive study, the researchers settled on meloxicam, widely used in zoos to treat raptors, as an alternative. They safety-tested it, then made their recommendation.

India banned the veterinary use of diclofenac in 2006. But diversion from human formulations persisted, prompting limits on package sizes in 2015. Other drugs similarly toxic to the vulture remained, some of which have been banned since 2022.

While the deep plunge has been arrested, the crisis continues.

A 2025 report by the research body Wildlife Institute of India, based on nesting-site counts, suggests that vultures have disappeared from nearly 75% of historical nesting sites in the country (although they have appeared in some new ones). Nesting sites are now dangerously concentrated, with two states, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, holding nearly half the breeding population.

Within Madhya Pradesh, nearly a third of the Indian vulture breeding population nests in Panna.

***

Panna — forest, grassland, gorge — is among the most beautiful landscapes I have seen.

It unfolds as a chain of plateaus, the highest rising to about 500 metres above sea level, before dropping sharply towards the Ken River near the Madla zone.

We entered the reserve at this high plateau, and were met almost instantly by a beguiling scent; our guide explained it came from American Mint, an invasive that no animal will eat, and that smothers the edible grasses around it. Beauty, here, was a cloak for danger.

Our next safari took us to the Hinauta zone, halfway down and pressed up against a diamond mine. Panna — so lovely, so valuable — felt hemmed in on all sides: by farms, villages, mine and river. That morning, thick mist blanketed the grassland, lending the place an otherworldly beauty. Our chatty guide was in the middle of describing the park’s efforts to sensitise local schoolchildren to wildlife when we saw her: an orange-and-white ghost slinking through the mist. For a moment, the world narrowed to just her and us, and then she walked away along the dry streambed, melting back into the mist.

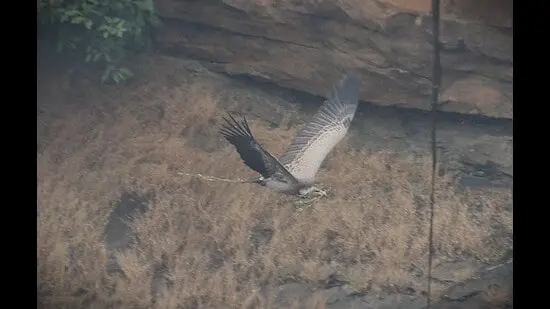

Our guide then took us to Dhundua Seha or Vulture Point. Below us lay a giant semi-circular “amphitheatre” of striated brown rock sculpted by the Ken over centuries. I saw vultures flying across — many solitary, some in pairs — carrying grasses and twigs to build their nests in the crevices of the cliff. They are, after all, social birds, and build nests close together. How few understood the wonder before us: the remnants of the remnants, the survivors charged with raising the next generation. But eager to “sight” the next tiger, we moved on.

Charisma matters. Gyps vultures are listed as Critically Endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List; the tiger, by comparison, is now merely Endangered. Yet the tiger commands attention, reverence even. Everyone holds their breath when one is nearby; time slows, as the orange stripes move through the brush.

The vulture, by contrast, is a bald, unsexy bird, hovering awkwardly over rotting carcasses. Important, but hard to love.

***

The absence of these birds in intact habitats and carcass dumps is worrying, suggesting their populations have dipped too low and are not recovering, perhaps because of the continued presence of vulture-toxic drugs.

Their lifecycle adds to the problem. “Vultures lay one egg a year. Only half the chicks reach adulthood,” Prakash says. “They start breeding at the age of five or six. If adult mortality rises above 5%, extinction becomes possible. During the diclofenac years, mortality exceeded 40%. That was catastrophic.”

Their loss hurts us.

A University of Chicago study titled The Social Costs of Keystone Species Collapse: Evidence from the Decline of Vultures in India, examined a range of data from 1988 to 2005 and found that, in districts where this bird previously thrived, all-cause human death rates increased by over 4% following its near-extinction. This translated to 104,386 additional annual deaths across the sampled population.

This “sanitation shock” was a result of Nature, which abhors a vacuum, plugging the hole left by vultures in less salubrious ways. The study, published in 2024, found a rise in sales of anti-rabies vaccines, a marker for rise in feral-dog populations in vulture-friendly districts. Anant Sudarshan, an economist and co-author of the paper, told me stray dogs alone do not account for all the additional deaths. Rising rat populations and falling water quality contribute hugely too, with urban areas hit harder.

A grainy photograph from 1980s Delhi shows hundreds of vultures congregated over what looks to be a carcass dump. Fast-forward to today, and dogs maraud at festering sites. Vultures are uniquely adapted to deal with carrion: bald heads that stay clean; extraordinarily acidic stomachs to keep infection contained. Their substitutes are not as well-adapted. Even if we adapt to stray dogs (with vaccines), rats and poor water quality, the toll on productivity and quality of life will continue.

There are efforts to help them recover. BNHS, together with forest departments and other research organisations, has set up captive-breeding sites, of which the one in Pinjore has been the most successful. Early this year, 34 vultures from here were released into the wild in Maharashtra. While some have been lost, Prakash remains hopeful. “Vultures can adapt. They will not return to past numbers, but they can be kept from going extinct. We know how to breed them and how to reintroduce them. But toxic drugs must be banned immediately, and any new molecule should be tested on scavenging birds before being introduced. That is key to ensuring vultures survive.”

Returning to the story we began with, the brother who Sampati protects is Jatayu, the bird that tries to rescue Sita from Ravana and dies; the only being Rama ever performs funeral rites for.

I wonder what he would make of the plight of his kinsman’s kin today.

(Mridula Ramesh is a climate-tech investor and author of The Climate Solution and Watershed. She can be reached on [email protected]. The views expressed are personal)