The world needs a lot more memory chips and hard drives. The companies making those products have very good reasons not to rush the job.

The boom-and-bust memory business has been enjoying its biggest boom in years—perhaps ever. The rapid build-out of infrastructure for artificial intelligence is consuming a large portion of available supply of NAND flash memory, DRAM memory and hard drives. That has resulted in a shortage of memory for other markets such as PCs and smartphones. “Memory is in the midst of a generational supply and demand mismatch,” Morgan Stanley chip analyst Joe Moore wrote in a report last month.

Tight supply is driving up prices and sharply boosting revenue and earnings for memory producers. Micron posted record quarterly revenue and operating income last month, while Samsung said Thursday that its fourth-quarter operating profit is expected to triple on a year-over-year basis.

A severe market shortage accompanied by sky-high prices would normally compel manufacturers to sharply boost their production. But memory companies have been burned by sharp price swings in the past and will therefore be cautious in their response this time.

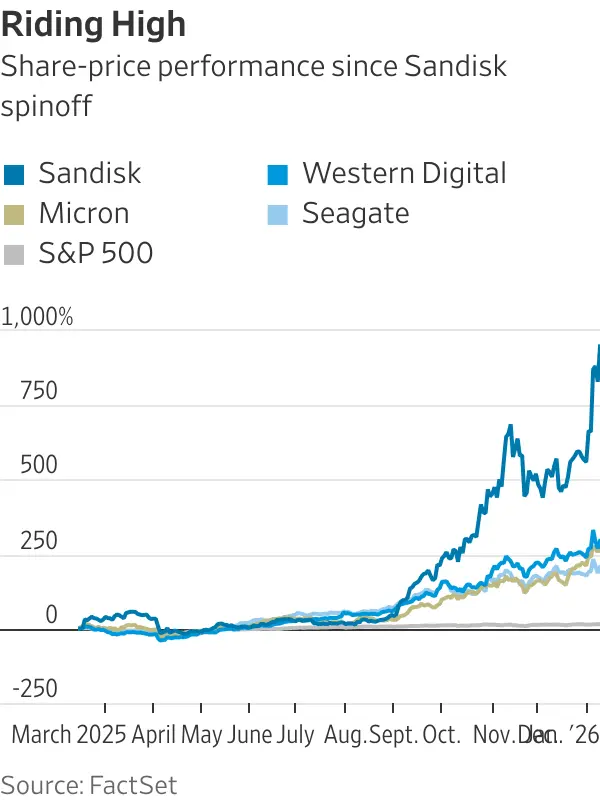

They have a strong incentive to do so, as memory stocks have become a hot commodity on Wall Street. Micron, Seagate and Western Digital saw their stock prices more than double in 2025 and were the biggest gainers on the S&P 500 for the year. Flash memory maker Sandisk has soared 10-fold since spinning off from Western Digital in February. SK Hynix, the South Korean chip maker that is focused exclusively on memory, is up 88% in just the past three months.

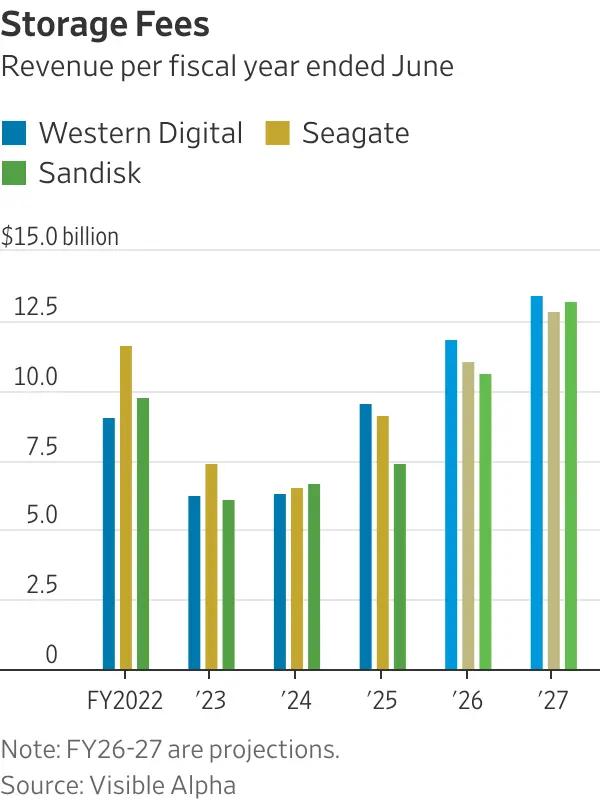

Analysts expect prices on memory chips and hard drives to remain high this year, which will likely help sustain those elevated market values. But the industry has a long history of brutal cycles, where downturns in pricing can often take producers into the red and sink their stock prices. The last one happened in 2023, when Micron, Western, Seagate and Hynix all produced annual operating losses.

Will this time be different? It could be. The AI computing systems designed by companies like Nvidia and Advanced Micro Devices require gobs of specialized DRAM to perform their functions. Those functions also create reams of new data that has to be stored on components like hard drives and flash-based solid-state drives.

This has created a “data explosion,” according to Bernstein analyst Mark Newman, who projects total data-storage shipments between NAND flash and hard drives will average 19% annual growth over the next four years, compared with a 14% average growth rate over the past 10.

Nvidia and AMD have also accelerated their own product cycles, introducing significant new systems every year now. Boosting the DRAM memory on those systems helps improve the overall performance over previous generations; Nvidia said its Rubin GPU chips unveiled this past week at the Consumer Electronics Show nearly triple the memory bandwidth compared to the Blackwell chips it started shipping last year.

Demand for such systems is ultimately powered by capital expenditures by the world’s largest tech companies. That has already reached nosebleed levels but isn’t yet showing any signs of slumping. Based on estimates for the December-ended quarter, total capital spending by Amazon.com, Google, Microsoft and Meta Platforms hit $407 billion in 2025.

Analysts expect that to jump to about $523 billion this year, according to consensus projections from Visible Alpha. “If demand stays this robust, the upcycle could continue for multiple years,” wrote Morgan Stanley’s Moore.

But memory executives are ever mindful of past downcycles. So despite dire projections of memory shortages for other types of electronics, producers like Micron, Sandisk, Seagate and Western will proceed cautiously in adding new production capacity. Only Seagate is planning a substantial increase in its own capital expenditures this year, and that is only to keep the company’s capital intensity around its historic level of about 4% of revenue.

Sandisk is expected to grow its own capex by 18% for the fiscal year ending in June despite a 44% surge in revenue for the same period, according to FactSet estimates. At a UBS conference last month, Sandisk Chief Executive David Goeckeler said the lack of long-term supply agreements in much of the NAND flash industry makes it challenging for companies like his to make long-term investment decisions. Like other types of semiconductors, NAND flash chips require facilities that can take years to build.

“Perhaps the demand side should think about making commitments that are longer than three months at a time,” Goeckeler said at the conference. He added that “we need to get the economics right to be able to continue to invest that money and not go through these huge episodic periods of losing money.” Some memories burn brighter than others.

Write to Dan Gallagher at [email protected]