The Arabian Nights stories and even the relation of them have given rise to a number of puzzles, with one of the best known being adding up grains of wheat placed in geometric progression on the 64 squares of a chessboard. We will not go into something so basic in Problematics.

I found an interesting one in a book of puzzles I bought as a student several decades ago. Edited by the late puzzler David Pritchard, the compilation contains an Arabian Nights-themed puzzle whose working is somewhat similar to another puzzle, not related to the Arabian Nights, that appeared during the first year of Problematics in HT. I have repackaged the puzzle from Pritchard’s book in a setting outside of ancient Arabia.

#Puzzle 179.1

The family of a child weak at mathematics engages an expensive private tutor who is willing to put in a number of hours every day. The catch, of course, is that she charges by the hour: ₹60 per 60 minutes, with additional minutes also counting at the same rate (for example, ₹61 for 1 hour and 1 minute).

She sets down her terms: she will work seven days every week, putting in as many hours as necessary. She will never work on 31 December, because she wants to celebrate. She will never work on 29 February either, because that is her birthday and comes only once every four years. She will take a month’s leave every year. There will no charge for this month on leave or for 31 December. She will receive her annual payment on 30 December every year.

On the first day, 1 January, she spends 3 hours and 19 minutes getting acquainted with her student. At the end of the session, she asks him: “Suppose I take a month’s leave in September this year, then in October next year, and again in November the year after that. I will not work on 31 December in any of these years, nor on February 29 in any leap year. If every day’s class takes 3 hours and 19 minutes like today, what will my total bill for three years come to?”

Blank stare from the young child who, as we know, is weak at mathematics.

The teacher is a good one, however. At the end of three years, her student is topping his class. On 30 December of the third year, she winds up a class that took 2 hours and 11 minutes. “As I had predicted, I took my month’s leaves in September in the first year, in October in the second year, and November in the third year. Suppose every class not counting my yearly holidays on 31 December (and on 29 February wherever applicable) took us exactly 2 hours and 11 minutes. What would my total bill for three years have come to?”

The boy gives the correct answer in a flash, without using a calculator.

“And suppose every class had lasted 3 hours and 19 minutes, as on the first day?”

The boy again answers without a moment’s hesitation: “Your bill for three years would have been ₹…”

“As it is, after collecting this year’s pay,” the teacher continues, “I will have received ₹1 lakh 65 thousand and 165 over a period of three years. It is money well earned, considering the progress you have made.”

“That is an average of _ hours and __ minutes per daily class,” says the boy, again without consulting a calculator.

Can the reader too do these calculations without using a calculator? What method does the boy use?

#Puzzle 179.2

When gambling fairs used to be common in towns across the country, one game involved a pair of dice with customers betting on the outcome. The stall-keeper would roll both dice, and the customer would bet that the sum of the spots shown up on the top would be “less than 7“, or “more than 7“. Double the money if right, money lost if wrong. In addition, the customer could also bet that the total on the two dice would be “exactly 7“. Triple the money if correct.

What is the probability of winning each kind of bet?

MAILBOX: LAST WEEK’S SOLVERS

#Puzzle 178.1

Hi Kabir,

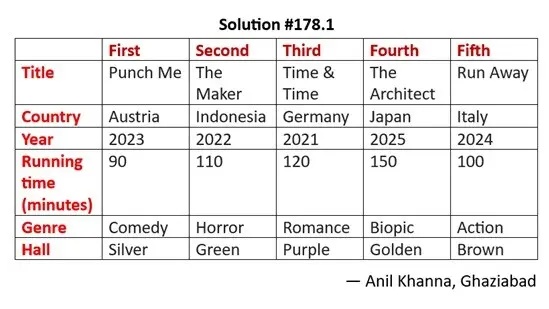

The film watching schedule is as shown in the table.

— Anil Khanna, Ghaziabad

#Puzzle 178.2

Dear Kabir,

They can watch 2 movies with a blue pass, 4 movies with a red pass, and 5 movies with a yellow pass.

Let these numbers be b, r and y respectively. Given 3b + r = 2y, and b + 2r + 3y = 25.

Taking y = (3b + r)/2 from the first equation and substituting this value in the second equation,

b + 2r + 3(3b + r)/2 =25

=> 2b + 4r + 9b + 3r = 50

=> 11b + 7r = 50

For integer solutions, this is feasible only with b = 2 and r = 4.

This gives y = (3*2 + 4)/2 = 5

Thus b = 2, r = 4 and y = 5.

In the puzzle, the word “they” should have been “he or she”. The use of “they” initially caused some confusion.

— Yadvendra Somra, Sonipat

Solved both puzzles: Anil Khanna (Ghaziabad), Yadvendra Somra (Sonipat), Amarpreet (Delhi), Kanwarjit Singh (Chief Commissioner of Income-tax, retired), Ajay Ashok (Delhi), Shishir Gupta (Indore)

Solved #Puzzle 178.1: Sabornee Jana (Mumbai)

Solved #Puzzle 178.2: Dr Jeffrey R Geist (Columbus, Ohio), Vinod Mahajan (Delhi), YK Munjal (Delhi), Dr Sunita Gupta (Delhi), Shri Ram Aggarwal (Delhi)

Last week’s Einstein puzzle was tougher than usual. Thanks to everyone (including Vinod Mahajan, Dr Sunita Gupta, and Shri Ram Aggarwal) who tried to crack it but made one or two mistakes.