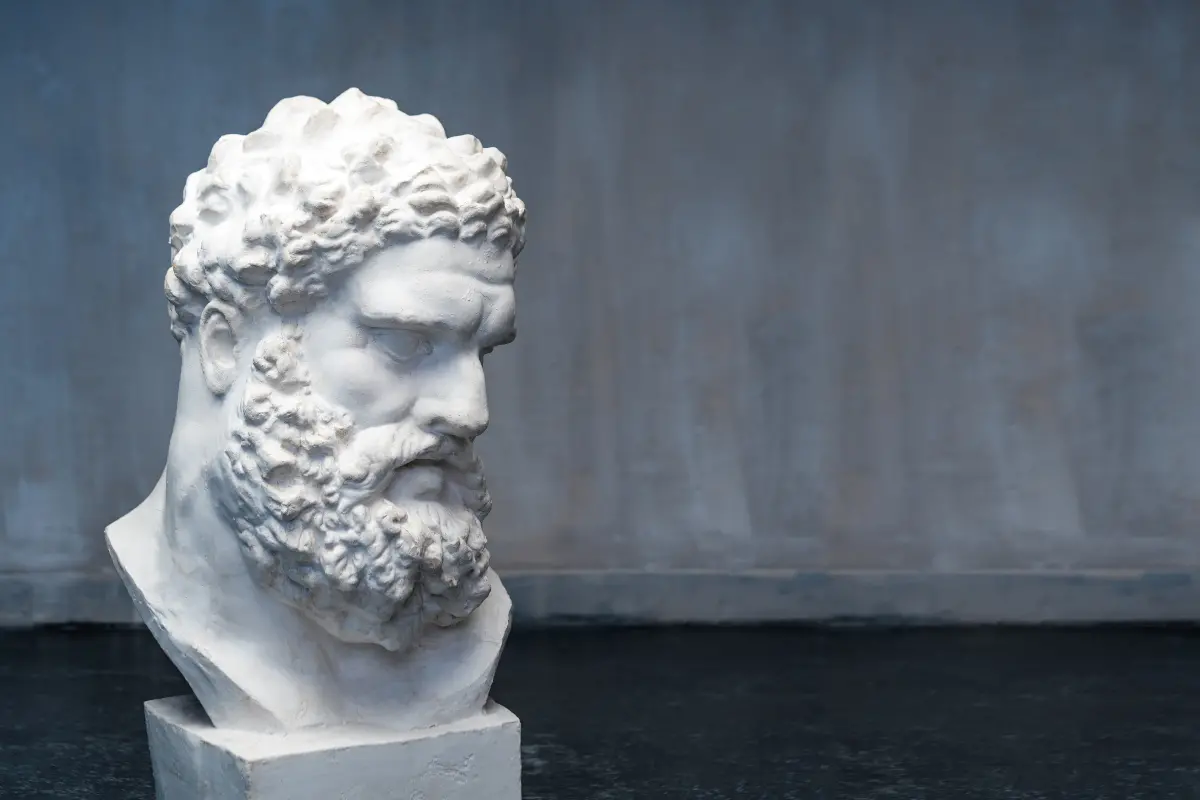

Hercules, known as Heracles in Greek mythology, stands as an emblem of heroism, strength, and perseverance. Embodied in his legendary twelve labours, his story is one that transcends time, offering a glimpse into the ancient ideals of Greek heroism that continue to fascinate and inspire audiences today.

The tale of Hercules begins with his divine lineage—as the son of Zeus, the king of the gods, and Alcmene, a mortal woman. Being the offspring of a god and a mortal, Hercules was granted an extraordinary life filled with both privilege and adversity. From his very birth, Hera, the jealous wife of Zeus, sought to destroy him, marking Hercules' life with a series of challenges designed to thwart his existence.

Despite Hera's machinations, including sending serpents to kill him in his cradle, Hercules' inherent might was evident even as an infant when he strangled the snakes with his bare hands. This act foreshadowed the numerous feats of strength that would define his life as a quintessential hero. Hercules' exploits are not merely displays of raw power; they reflect a series of moral and physical trials shaping the concept of Greek heroism.

Among the feats Hercules is most renowned for are the Twelve Labours—a series of tasks so perilous and difficult they seemed impossible for mortals to complete. These labours were imposed on him as a penance and a way to attain immortality, a path walked by few in Greek mythology. The tale of these labours unfolds as an epic narrative of redemption and transformation, making Hercules an enduring symbol of the hero's journey.

The Nemean Lion, whose hide was impervious to weapons, was Hercules' first labor. He suffocated the beast with his bare hands and, in a subsequent display of ingenuity, used the lion's own claws to skin it. This pelt would become a distinctive element of his iconography. Lernaean Hydra, a serpent with many heads that could regenerate two for each cut off, was next. Hercules used both strength and assistance, enlisting his nephew Iolaus to help cauterise the heads, preventing them from regrowing. This task showcases the recurring theme that Hercules, despite his might, did not always work alone; his labours were also tests of his ability to plan and accept help.

His other labours range from capturing alive the Golden Hind of Artemis—a symbol of his piety and respect for the gods, given that he accomplished this without harming the sacred animal—to cleansing the Augean stables in a single day, which he did by rerouting two rivers to wash away the filth, demonstrating his cleverness alongside strength.

Not all of his labour involved combat or feats of strength. Some, like obtaining the girdle of the Amazon queen Hippolyta, started as peaceful quests that only became battles because of the manipulations of the gods, revealing the constant divine interference in his life. Even these conflicts, however, served a purpose in the mythological narrative: they demonstrated Hercules' resilience against the whims of the gods and the untamed chaos of nature and the world.

Hercules' story is not limited to his labors. His life was filled with other remarkable incidents, from his role in the Argonauts' quest for the Golden Fleece to his adventures across the known world, each adding layers to his character as a hero. He encountered and often bested many of the fearsome creatures that make Greek mythology so vibrant and otherworldly.

In addition to his physical prowess, Hercules is often depicted as having a good heart—he was kind, sometimes vulnerable, and inevitably human in his emotions. Despite some portrayals of him as brutish and unaware, many stories emphasise his wisdom and wit. His heroic narrative is also tinged with tragedy. Hercules married multiple times, his most famous wife being Deianira, who was inadvertently the cause of his mortal end—an end that, like many aspects of his life, was orchestrated by Hera.

The death of Hercules is as significant as his life. After being poisoned by the blood of the centaur Nessus through a tunic Deianira sent him, believing it contained a love charm, Hercules chose to end his suffering by immolating himself on a funeral pyre. This dramatic act led to his apotheosis—the process by which a mortal becomes a god—culminating his story with the hero's ascension to Mount Olympus, joining the gods in immortality.

Hercules' legacy influences our modern understanding of heroism, reflecting enduring values of bravery, determination, and cleverness. The hero illustrated that true heroism lies not solely in physical strength but also in one's moral compass and the ability to face adversity with courage.

Today, Hercules occupies a revered place in cultural memory, with his tale being retold through numerous mediums—literature, art, theatre, and film. His influence is not fleeting; it lives on, a testament to the timeless allure of Greek mythology and the concept of heroism it crafted. Hercules remains a model of heroism centuries after his mythical exploits, a reminder that heroes, even in their flaws, represent the best of what we aspire to be.