Five new exoplanets have been discovered—each of them so young, they are still growing.

The baby planets were discovered by researchers in the midst of an international planet hunt, using a new advanced imaging technique that allowed the detection of planets and solar systems that had previously been obscured by gas and dust.

Rather than looking for a planet's direct light, it searches instead for the effects that planets have on their surroundings.

"This is a totally new area of research and a really wonderful dataset," astrophysicist professor Daniel Price of Monash University, Australia—who helped develop the technique—told Newsweek.

He added: "It is only since 1995 we discovered that solar systems exist around stars other than the Sun, and now we are finally getting a glimpse of how these extra-solar planets are formed."

Primary investigator professor and fellow Monash astrophysicist Christophe Pinte said in a statement that the approach is "like trying to spot a fish by looking for ripples in a pond, rather than trying to see the fish itself."

The work is part of exoALMA, an international project to find new planets, with the new approach allowing researchers to find planets 1,000 times younger than Earth—as young as a few million years old.

In contrast, our own planet is thought to be around 4.5 billion years old, according to The Planetary Society: it was born in the early days of our Solar System, which began forming an estimated 4.6 billion years ago.

exoALMA is named after a powerful telescope in Chile which can capture images of never-before-seen planets and their solar systems: the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA).

Pinte, who pioneered the new technique, explained that being able to detect much younger planets allows researchers to "learn a lot more about how they grow and evolve.

He added: "A key finding of exoALMA is that planets form quickly, in less than a few million years, and in surprisingly dynamic environments, with many physical mechanisms at play."

It allows both a higher understanding of how planets interact with their environments and evolve over time, as well as the potential to learn more about how our own planet formed and developed.

Price explained that more than while some 5,000 exoplanets have already been discovered, they are all mature systems.

Thus, they can not help researchers to understand "how they formed or why they differ so drastically from our own solar system."

He called their new technique "a remarkable leap forward for astronomy, and [it] opens up lightyears of new possibilities for future discoveries."

"By uncovering the youngest planets, exoALMA is providing the first clues to unravel these mysteries."

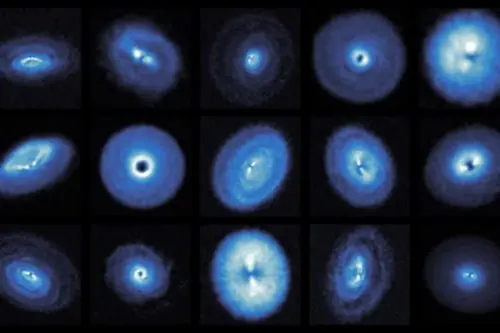

Price told Newsweek: "How planets are born is an unsolved area of research, and the new set of observations helps us understand how planets form and grow in discs of gas and dust around young stars. This is the first time we've had very high resolution observations of the gas motions in these 'protoplanetary discs', and there are clear signatures of planets from the spiral arms they create."

Their findings have been published in 17 papers in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, with more to come later in 2025. The data and images connected with the research is to be made publicly available, in order to support further scientific discoveries.

Price told Newsweek they are currently in touch with NASA's James Webb Telescope "to try to image the planets directly, and planning more observations to look for chemical imprints where the newborn planets warm their surrounding gas, to try to get an idea of how fast they grow."

He concluded: "It's a very fast-moving field."

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about space? Let us know via [email protected].