Campbell’s Tomato soup

They sit quietly on supermarket and grocery store shelves, as well as in kitchens and office pantries. Most shoppers place them into their carts with little thought beyond flavour, brand, and price. Common examples include canned tuna, chickpeas, tomatoes, and soups, alongside bottled green juices, yoghurt drinks, kombucha, and vitamin-infused waters.

Few food items are as widely used or as casually consumed as canned foods and bottled health drinks. Many households depend on them as regular staples. For busy families, they offer quick meals, protein on the go, or an easy nutrient boost without cooking. Despite their everyday presence, consumers often focus more on convenience and taste than on nutritional content.

Packaging has evolved to signal wellness and health benefits. The question remains: how much do we truly know about what is inside these cans and bottles?

Convenience and the Nutritional Grey Zone

From a nutritional perspective, these foods sit in a middle ground. They are neither fast food nor fully unprocessed. Their long shelf life makes them useful when fresh foods are unavailable. In return, they promise nourishment with minimal effort.

Several questions naturally arise. How much nutrition survives canning? Do bottled juices and wellness drinks genuinely support health, or are they sweetened beverages dressed up as functional foods? Should these staples be viewed as nutritional allies or carefully marketed compromises?

As interest in healthier lifestyles grows, closer attention to everyday food choices becomes essential. Understanding nutritional value helps consumers balance convenience with long-term health.

The Origins of Canned Food

Canning developed in the early nineteenth century as a solution for feeding armies and explorers. In France, shortly before the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon Bonaparte recognised the damage poor nutrition caused among soldiers. In 1795, he introduced the Preservation Prize, offering 12,000 francs to anyone who could improve food storage methods.

By 1809, French food preserver Nicolas Appert observed that food cooked and sealed in airtight containers did not spoil unless the seal failed. He refined a process that used heat to kill bacteria and extend shelf life from days to years. Over time, what began as a military solution became a mainstream method of food preservation.

Glass Saltshaker isolated on white background with clipping path

What Happens to Nutrients During Canning

From a nutritional standpoint, canned foods involve both benefits and compromises. The canning process heats food to temperatures between 116°C and 130°C to destroy harmful microorganisms. As a result, some heat-sensitive nutrients, including vitamin C and certain B vitamins, may decline.

Most macronutrients and minerals, however, remain stable. Protein, carbohydrates, fats, fibre, calcium, and iron largely survive the process. Canned beans retain nearly the same protein and fibre as freshly cooked beans. Canned tuna continues to provide lean protein and omega-3 fatty acids.

Canned tomatoes, often criticised for sodium content, contain higher levels of lycopene than fresh tomatoes. Heating breaks down plant cell walls, making this antioxidant easier for the body to absorb.

Canned Fruits and Added Sugars

Canned fruits packed in water or natural juice can deliver vitamin levels similar to fresh fruit, particularly when processed soon after harvest. Some loss of vitamin C may occur, but fat-soluble vitamins such as A and E remain relatively stable.

Problems arise when fruit is packed in syrup or sweetened juice. These options add unnecessary sugar and calories, reducing overall nutritional value.

The Sodium Trade-Off

Sodium remains one of the main concerns associated with canned foods. Salt enhances flavour and preserves texture, but excessive intake links to high blood pressure and increased cardiovascular risk.

A single serving of canned soup may contain 800 to 1,000 milligrams of sodium, close to half the recommended daily intake. Added sodium also appears in vegetables, beans, and meats during processing or brining.

Food preservation methods have improved over time. Many brands now offer low-sodium, reduced-sodium, or no-salt-added options. Rinsing canned beans or vegetables under running water can lower sodium content by up to 40 percent. This simple step improves nutritional quality while maintaining convenience.

Re-examining the Myth of Inferiority

Canned food has long carried a reputation for being nutritionally inferior. Recent research challenges this assumption. Many canned fruits and vegetables are processed at peak ripeness, when nutrient levels are highest.

Fresh produce may lose nutrients during transport and storage. In some cases, canned foods retain more nutrients than their fresh counterparts. Canned pumpkin and sweet corn often match or exceed fresh versions in carotenoid content.

Canned fish such as sardines and salmon provide omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, and calcium from softened edible bones. These nutrients support bone strength and cardiovascular health. Canned legumes, including kidney beans, chickpeas, and lentils, remain rich in protein, fibre, folate, and complex carbohydrates. Their affordability and long shelf life make them valuable dietary staples.

flat lay juice bottle with spinach leaves

Packaging and BPA Concerns

Packaging has also influenced public perception of canned foods. Bisphenol-A (BPA), once widely used to line metal cans, raised concerns after studies linked it to metabolic, cardiovascular, and developmental effects.

Consumer demand led many manufacturers to adopt BPA-free linings. As a result, BPA exposure from canned foods has declined in recent years. The European Union has banned BPA in food contact materials from January 2025.

Those wishing to minimise exposure can select BPA-free products or choose foods packaged in glass.

Portion Size and Energy Density

Canned foods can blur portion awareness. Labels often define a serving as half a can, yet many people consume the entire container.

This matters most for calorie-dense soups and stews. In contrast, canned vegetables, beans, and fish tend to remain low in calories and rich in nutrients. Their high water content also promotes fullness and may help with weight management.

Reading labels, rather than avoiding canned foods altogether, remains the most effective approach.

Canned goods display in a supermarket

The Rise of Bottled Health Drinks

If canned foods symbolise convenience in meals, bottled health drinks represent shortcuts to nutrition. Supermarket shelves now feature juices, protein shakes, kombucha, vitamin waters, and fortified beverages.

Marketed as energising and nourishing, these drinks appeal to consumers seeking wellness without preparation. The global functional beverage market has grown rapidly, but nutritional quality varies widely.

Bottled Kombucha

Juices and Smoothies

Bottled fruit juices lack fibre and concentrate natural sugars. A 350-millilitre bottle of orange juice contains similar calories and sugar to a soft drink.

Even cold-pressed juices can cause rapid blood sugar spikes. Without fibre, sugar absorbs quickly and places stress on metabolic control.

Smoothies offer better balance when they retain pulp and include protein or healthy fats. However, many commercial versions add sweeteners, concentrates, or stabilisers, turning them into high-calorie drinks rather than balanced meals.

Vegan Protein Shake

Protein Shakes

Protein shakes can benefit people with higher protein needs, such as athletes, older adults, or individuals recovering from illness. A quality product typically contains 15 to 25 grams of protein with minimal added sugar.

Most sedentary adults meet protein requirements through regular meals. For them, protein drinks often add unnecessary calories. Many products also include syrups and flavourings that undermine health claims.

Short ingredient lists generally indicate better nutritional quality.

Vitamin Waters and Fortified Beverages

Vitamin waters promote hydration with added micronutrients. While they contain vitamins, most people already meet daily requirements through food.

Many versions include added sugars or sweeteners. Vitamin content may degrade over time, particularly with light and heat exposure. Frequent consumption may also affect dental health due to acidity.

Plant-Based Milks

Plant-based milks vary widely in nutritional value. Unsweetened soy milk provides protein comparable to dairy. Almond and rice milk contain minimal protein and are mostly water. Oat milk offers soluble fibre but more carbohydrates. Coconut milk supplies fast-burning fats but also contains saturated fat.

Most brands fortify these drinks with calcium, vitamin D, and B12. Unsweetened versions remain the healthiest choice.

Smoothie. Healthy fresh raw detox spinach smoothie with green apple, kiwi and ginger in a bottles on a table. Healthy diet vegan food full of antioxidants

Fermented Drinks and Kombucha

Fermented drinks may support gut health if they contain live cultures. Some bottled versions undergo pasteurisation, which removes beneficial bacteria.

Others add fruit juice for flavour, increasing sugar content. Refrigerated, low-sugar options offer greater probiotic potential.

Calories and the Illusion of Health

Liquid calories are easy to overconsume. Sweetened drinks can quietly add hundreds of calories per day.

Many bottled beverages also contain stabilisers, preservatives, and artificial flavours. While generally safe in moderation, these additives add no nutritional value and may irritate sensitive digestive systems.

Hydration Versus Nutrition

Hydration and nutrition serve different roles. Most people meet fluid needs through water and food. Nutrition requires balance between macronutrients and micronutrients.

Functional beverages often focus on single nutrients, oversimplifying dietary needs. Whole foods provide more reliable benefits.

What Science Says About Long-Term Health Effects

Long-term nutrition studies consistently show that moderate consumption of canned foods can fit well within healthy dietary patterns. This is especially true when the overall diet remains rich in whole grains, fresh produce, and lean proteins.

A multi-year analysis published in Nutrients found that adults who regularly included canned vegetables, beans, and fish in their meals achieved higher overall intakes of key nutrients. These included fibre, potassium, calcium, and omega-3 fatty acids. In comparison, individuals who relied solely on fresh or frozen sources tended to consume lower amounts of these nutrients.

Why Accessibility Matters

One major reason lies in accessibility. Canned foods are typically harvested and processed at peak ripeness, when nutrient density is highest. They also provide year-round availability, regardless of season or cost.

For people with limited access to fresh produce or demanding schedules, canned foods can help close nutritional gaps that might otherwise persist.

Canned fish such as sardines, mackerel, and salmon are particularly well supported by research. These foods retain their omega-3 fatty acid content during processing. They also often provide higher calcium levels than fresh fish due to their softened, edible bones.

Studies conducted in Japan, the United States, and Europe show that people who eat canned fish at least twice a week are more likely to meet recommended EPA and DHA intake levels. These fatty acids are strongly associated with improved cardiovascular health.

Similarly, canned legumes remain excellent sources of plant-based protein and folate. Rinsing them before use reduces sodium content without causing significant nutrient loss. Together, these findings reinforce a broader principle in dietetics: the health impact of canned food depends more on product choice and preparation than on the canning process itself.

The Long-Term Impact of Bottled Health Drinks

The picture looks very different for bottled health drinks. Many of these products are undermined by added sugars, stabilisers, and concentrated fruit bases.

Long-term cohort studies show a clear association between frequent consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and higher risks of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. Even drinks marketed as natural or energising, such as bottled smoothies, vitamin waters, and functional teas, can contain 20 to 35 grams of sugar per serving. In many cases, this approaches the sugar content of carbonated soft drinks.

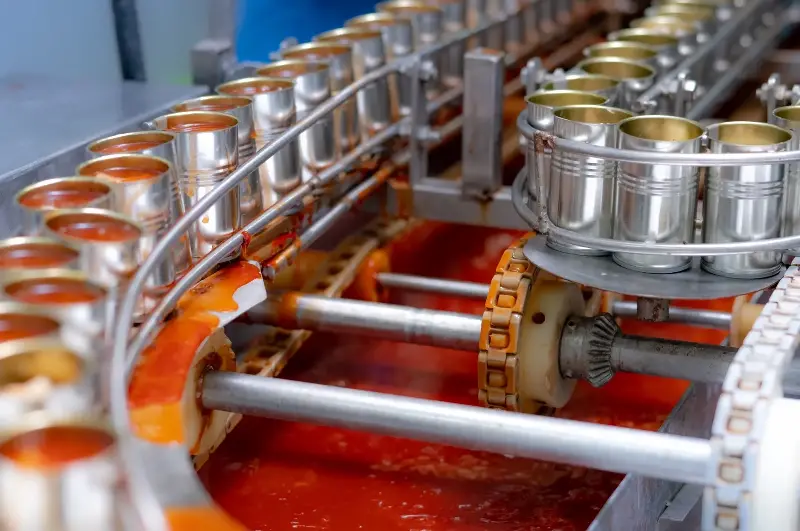

Canned fish factory. Food industry. Sardines in red tomato sauce in tinned cans at food factory. Food processing production line. Food manufacturing industry. Many can of sardines on a conveyor belt.

The Problem With Liquid Sugar

Global health authorities continue to warn about the metabolic effects of liquid sugar. The body absorbs sugar in liquid form rapidly and without the satiety benefits provided by fibre or protein.

The World Health Organisation advises keeping free sugar intake below 10 percent of total daily energy intake. This equates to roughly 50 grams per day for an average adult. For additional health benefits, it recommends limiting intake to under 25 grams, or less than 5 percent of daily energy.

Free sugars include those added to food and drinks, as well as sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, and fruit juices. Many popular bottled beverages deliver half of this recommended daily limit in a single bottle, encouraging passive overconsumption.

Overall, the evidence points to a clear distinction. Canned whole foods can support nutritional adequacy, while bottled sugary drinks more often undermine it. Long-term health outcomes depend primarily on what is inside the package.

The Smart Consumer’s Checklist CHOOSING CANNED FOODS

The Future of Processed Nutrition

Technology continues to blur the line between convenience and health. Innovations in canning and aseptic processing now make it possible to produce canned lentil stews with quinoa, vegetable mixes rich in phytonutrients, and low-sodium soups enhanced with resistant starch and soluble fibres to support gut health.

These products are not simply healthier versions of older staples. They reflect a broader shift toward nutrient-dense, ready-to-eat meals designed to approximate the nutritional quality of home cooking.

At the same time, bottled beverages are evolving beyond basic juices and teas. Many now incorporate plant polyphenols such as catechins, anthocyanins, and curcumin. Research has linked these compounds to reduced inflammation and improved metabolic resilience. Others include prebiotic fibres such as inulin, GOS, and resistant dextrin, which nourish beneficial gut bacteria and may support immune and digestive health.

Emerging Technologies in Food Science

Artificial intelligence and precision fermentation are accelerating this transformation. AI-driven nutritional modelling allows manufacturers to predict micronutrient interactions, optimise ingredient combinations for bioavailability, and tailor formulations to specific demographic needs. These may include ageing adults, athletes, or people with metabolic concerns.

Precision fermentation, already used to produce dairy-free whey proteins and micronutrients such as vitamin B12, enables the creation of highly targeted nutrients with consistent purity and sustainability. In the future, this technology may allow canned or bottled foods to include plant-based proteins designed for optimal digestibility or probiotics engineered to remain viable without refrigeration. Such advances could significantly expand access to gut-friendly nutrition.

Despite these innovations, nutrition experts continue to emphasise a principle supported by decades of evidence. Whole foods should remain the foundation of a healthy diet. Even the most advanced packaged foods cannot fully replicate the combined benefits of unprocessed fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and minimally prepared proteins.

Technology can enhance convenience and nutrient delivery, but mindful consumption remains essential. Balancing processed foods with fresh, diverse choices will continue to underpin long-term health.

Beyond the Label

Canned foods and bottled health drinks reflect the dual nature of modern eating. They reveal our desire for both convenience and wellness. These products are neither villains nor heroes. They are tools, and their impact depends on how we use them.

A can of beans or tuna can anchor a nutritious meal just as easily as a bottled smoothie can exceed daily sugar needs. Understanding how processing influences nutrition allows consumers to choose more wisely, balancing practicality with health.

In the end, true nourishment comes from awareness. The healthiest diets are not built on trends or eye-catching labels, but on informed, consistent choices. PRIME