When I lived in Australia, I frequently visited the Julia Gillard Library in our suburb. It wasn’t the cafés where students went to study — it was the public library.

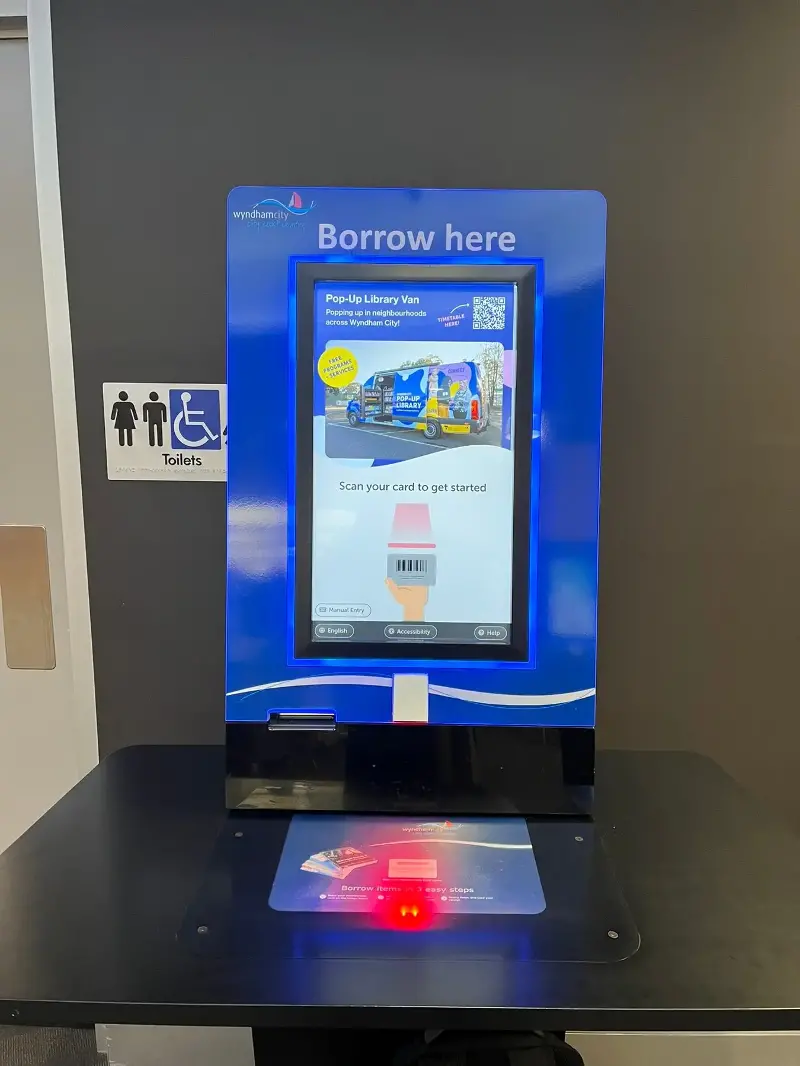

At home, I could hop on the library’s website, browse and reserve a book in minutes, and pick it up later. If I chose to drop by instead, I could use my library card to take them through a self-checkout counter, often without staff assistance. Returning the books was just as smooth as borrowing them.

Inside, the library welcomed everyone. It had large-print books for seniors and those with visual impairments, and audiobooks in multiple languages for its multicultural residents. Its shelves brimmed with both fiction and non-fiction titles that felt recent and carefully curated.

Reading needs physical space. A public library offers that space.

Also inside the library were public computers, silent study rooms, collaborative spaces, and a community center gathered people of various backgrounds for programs on education, mental and physical well-being, and social connection. It was heaven.

You couldn’t imagine the joy I felt in those two years.

Growing up, no one in our house read, much less read for leisure. Books were the least of my parents’ concerns, mainly due to financial limitations. When I was five, my aunt gave me a children’s dictionary, the first book I could call mine, apart from my school textbooks.

It’s no surprise that in 2023, 15-year-old Australians ranked ninth worldwide for reading. The country’s citizens continue to be among the highest users of public libraries per capita.

So when I returned to the Philippines, I felt a kind of reverse culture shock. We’ve grown used to the absence of public libraries, as if it were normal.

And yet, we often blame our youth’s low reading rates on laziness or love for dopamine-hit reels. But reading, like any behavior, develops through habit. It takes time. It needs repetition. And more importantly, it happens in space. Yes — a physical space.

A public library offers that space. It’s easy to read and reflect in a quiet room lined with books. But try doing the same in a cramped, noisy home with zero tomes.

And so we flock to cafés just to concentrate, as if we’re quietly admitting that silence and knowledge are a luxury. And here lies the dissonance.

Our public libraries in numbers

RA 7743 mandates every congressional district, city, municipality, and even barangay to establish a public library or reading center. Note the word: mandate. It’s not optional. It’s a legal obligation. And with our dismal transport system, placing a library within reach of every community is essential.

But the June 2025 figures from the National Library of the Philippines (NLP) paint a troubling picture: only about 4% of LGUs have public libraries. Out of over 44,000 LGUs nationwide, just 1,721 public libraries are affiliated with the NLP.

An earlier piece used NLP’s 2018 data, yet in the six years since, coverage has increased by only about a percentage point.

Public Libraries vs Local Government Units in the Philippines (June 2025)

| LGU Level | Total LGUs | NLP‑Affiliated Libraries | % Coverage |

| Congressional Districts | 253 | 3 | 1.2% |

| Provinces | 81 | 56 | 69.1% |

| Cities | 149 | 116 | 77.9% |

| Municipalities | 1,493 | 614 | 41.1% |

| Barangays | 42,011 | 928 | 2.2% |

| Regions (not mandated by RA 7734) |

— | 1 | — |

| Total | 43,987 units | 1,721 libraries (including 3 locally funded projects) | 3.9% |

Some critical numbers worth pondering:

- Only 3 out of 253 congressional districts have libraries

- Just 2% of barangays (928 out of 42,011) have reading centers

- 78% of cities have libraries, while only 41% of municipalities do — and we’re not even discussing regional disparities yet

But even existing libraries face steep challenges. Although the 2023 National Readership Survey found that 74% of Filipinos still prefer printed books and 89% view reading positively, a peer-reviewed study conducted the same year in Iloilo revealed a different reality on the ground: the 11 public libraries studied remain largely unused and underdeveloped.

Why the disconnect? The reasons are familiar: outdated and unorganized collections, limited staffing, lack of modern equipment, poor access for people with disabilities, and underfunding.

But a major reason stood out: people simply didn’t know these libraries existed.

And it’s not just in Iloilo. Six years before this, the same readership survey found that only 1 in 10 Filipinos knew of a library near their residence. Awareness dropped further at the barangay level, where only 12% knew a nearby library existed. Even in cities and municipalities, fewer than half could confirm if their area had one.

Why the silence?

Early this year, the Second Congressional Commission on Education (EDCOM II) found that over half of early-grade students (Grades 1 to 3) had reading levels that didn’t match their grade level. Meanwhile, around 1.7 million learners were deemed “transitioning readers,” or those still struggling to reach full fluency and comprehension for their grade level.

It’s no wonder, then, that many high school graduates fall short of functional literacy. Our systems fail them right at the childhood level.

Yet even a bold initiative like EDCOM II — while rightly devoted to classrooms, textbooks, and teachers — remains largely mum on the pitiful state of our public libraries. This is a glaring oversight, especially in a country where most households and communities lack books and reading spaces.

A reading culture is not born in classrooms alone. It blossoms in an ecosystem of reading spaces, and public libraries are essential threads in that web.

Some argue that even if we built more libraries, people wouldn’t use them. But like the cultural misdiagnosis discussed earlier, this confuses apathy with invisibility. People can’t use what they can’t find, much less what doesn’t exist.

Economists call this a failure of induced demand: when public infrastructure is absent, hidden, or defective, the demand it might have awakened simply never materializes. People read when books surround them. They will come to libraries only if these are visible and well-designed to meet their needs.

This creates a feedback loop. When communities don’t use their libraries, there’s little pressure on local officials to fund and improve them. Underused libraries struggle to justify their existence, and without adequate funding or public support, they stagnate further. And so, the cycle repeats itself: underuse leads to underfunding, which breeds invisibility, and in turn ensures underuse.

But the cycle isn’t destiny. Reading is a learned behavior — and learning, by nature, implies the possibility of change. If we’re serious about nurturing a culture of reading, we must first create the spaces that make the habit possible and easier to sustain.

The crisis facing our public libraries should be front and center in our public discourse and policy debate. Otherwise, future generations will keep mistaking this absence for the norm. – Rappler.com

Cesar Ilao III was a research assistant at Monash University, Australia. He created @thirdreading, an online advocacy campaign that calls for greater awareness, accessibility, and development of reading spaces across the Philippines.