WHAT STARTED as a bitter, sacred drink in the temples of the Aztecs would, by the 18th century, become the breakfast of Spanish nobles — and later, the guilty pleasure of the world. Chocolate’s transformation from a rare curiosity to an everyday comfort mirrors the global story of taste, trade, and temptation.

THE FIRST SIP: AMERINDIAN ROOTS

Before the Spanish conquest, cacao was currency, offering, and ritual. Among the Mayans and Aztecs, it was mixed with spices, maize, and flowers — a drink of the gods rather than dessert. When Spanish settlers in New Spain (modern Mexico) first encountered it in the 1500s, they were hooked.

Missionaries fretted about its addictive pull — one Jesuit in 1589 warned that chocolate “corrupts the body and the soul” — but by then, everyone from nobles to mestizos to enslaved workers was sipping it. In bustling Ciudad de México, cocoa lozenges were sold on the streets, dissolved in hot water or atole (a corn dough drink), customised with cinnamon, chilli, or rose petals.

As Indigenous populations declined and local cocoa supplies dwindled, the crop’s centre shifted south to what’s now Ecuador and Venezuela — regions that would soon feed a booming global craving.

THE COLONIAL CACAO RUSH

By the 1600s, chocolate was a social currency across the Atlantic. The sweeter criollo cocoa from Caracas was prized by Spain’s elites, while the high-yield forastero variety from Guayaquil became the everyday choice for the working classes.

The trade was messy. Cocoa was smuggled across colonies, taxed (and untaxed), and stirred into an Atlantic network that linked enslaved plantation labour, European nobility, and colonial merchants. In one famous gift, the Duke of Albuquerque sent 22,000 pounds of chocolate — each pound wrapped in gold foil — to Spain’s royal family.

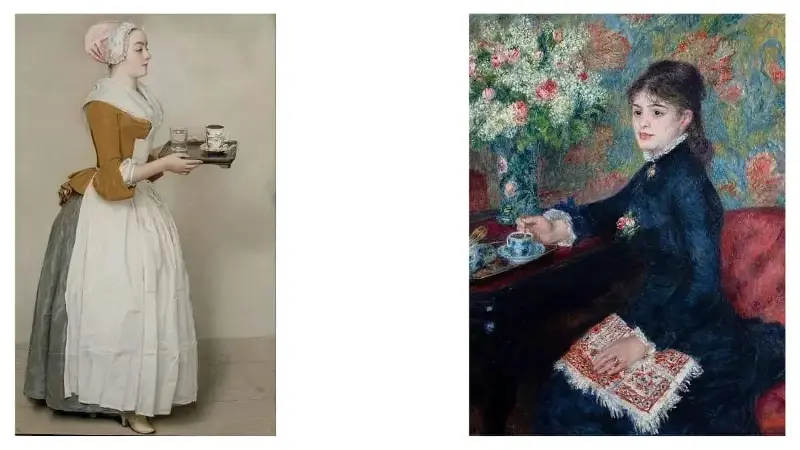

Soon, chocolate had its own rituals and gossip. Aristocrats competed over recipes, silver chocolate services gleamed at salons, and “having chocolate” became as social as drinking tea in England or coffee in France.

THE SPANISH CHOCOLATE ERA

As the drink gained popularity, Spain “Hispanised” chocolate — stripping away its “barbarous” origins and recasting it as a refined national treasure. The Spanish version was a blend of cocoa, sugar, and cinnamon, whipped until frothy. So famous was this recipe that even Diderot’s Encyclopédie noted: “Lacking chocolate in a Spanish home is like being too poor to have bread.”

But the drink wasn’t just an indulgence — it was an economic battlefield. Dutch merchants cornered much of the cocoa market through smuggling, forcing Spain to found the Guipuzcoan Company of Caracas in 1728 to regain control. The move reshaped the Atlantic trade, boosted production, and turned chocolate from elite luxury into a near-universal craving.

By the late 1700s, Madrid’s chocolate makers — the maestros molenderos — were everywhere, their grinding stones sweating under the heat. Street kiosks sold cheaper blends spiked with almonds or acorns, while wealthier homes ordered “labrada a la Italiana” — a premium brand made the Italian way.

A satirical Spanish folk song from the era captured the craze perfectly:

“Chocolate is now such a light breakfast

that even children in the barrios have their cup of chocolate.”

From cobblers to courtiers, chocolate had truly gone democratic.

FROM EMPIRE TO EVERYWHERE

By the late 18th century, Spain’s monopoly melted away, and free trade sent cocoa surging across the seas.

Guayaquil’s cheaper, hardier forastero variety began to dominate, outpacing the delicate criollo beans from Caracas. As wars and revolutions reshaped the map, cocoa’s roots spread further — to Brazil, Trinidad, the Dominican Republic, and eventually Africa.

By the early 1900s, the Portuguese colony of São Tomé and Príncipe and Britain’s Gold Coast (now Ghana) had become the world’s cocoa heartlands. Today, more than half of the world’s four million tonnes of cocoa still comes from sub-Saharan Africa, with the descendants of forastero beans making up over 80% of global production.

A GLOBAL ADDICTION

From divine offering to supermarket staple, chocolate’s 500-year journey is one of transformation — from sacred to sinful, from royal drink to mass comfort food. Every bar still carries the imprint of empire: Indigenous knowledge, European greed, African labour, and a universal craving for sweetness.

What began as the dark drink of the gods has become humanity’s most delicious vice.

This piece is adapted from “The Chocolate Route: The humble cocoa bean’s journey from its Amerindian origins to worldwide dominance” by Irene Fattacciu, published on Aeon (January 2022).