When I travelled through Himachal recently, what I noticed most, besides the usual shifts in landscape and temperature, was how the food seemed to have opened itself up to something broader–not through any deliberate fusion, but through a quiet adaptation to the people who had passed through and, more importantly, stayed. In Himachal, especially in the Parvati Valley, a large part of that story comes from Israeli travellers. Many arrive after completing their mandatory military service, and instead of moving constantly through the trail, they often stay in Himachal for extended periods.

Over time, this slow, quiet presence has become part of the region’s everyday rhythm. The Israeli food that appears on menus isn’t staged or themed; it’s practical, expected, and absorbed into the usual set of options. And what I found most interesting was that it wasn’t just Israeli tourists eating it. Indian travellers were ordering the same dishes, not as experiments, but because they had become part of what felt normal in that place.

Kasol: Where Indian And Israeli Tastes Share The Same Table

Kasol, being the easiest to reach among the villages I stayed in, also had the most cafés, and it’s probably where I began noticing the shift most clearly. Walking through the main market or along the river trails, menus offered an easy mix of foods that felt both local and imported, though not in a way that ever felt divided or confused. At cafés like Evergreen or German Bakery, it wasn’t unusual to see shakshuka listed right next to aloo paratha, or hummus offered alongside thukpa. And the people ordering those dishes weren’t always the Israelis who had become known for staying there; Indian tourists were just as present, eating falafel wraps with cold coffee, or dipping into bowls of tahini like it had always been there.

The seating would often be mixed too, with groups speaking Hindi and English on one side and Hebrew on the other, but all vibrating on the same wavelength. This wasn’t some trendy reinvention of pahadi cuisine, nor was it a deliberate attempt to recreate Israeli kitchens abroad. It was simply a case of food responding to who was eating it regularly, and the cooks adjusting accordingly. Over time, this adjustment stopped being a special effort; it had just become the new baseline.

Chalal: A Quiet Detour That Mirrors The Familiar

Just a short walk across the suspension bridge and into the trees, Chalal feels less hectic, but not disconnected. The music is slower, the dogs less frantic, and the cafés a bit quieter. I spent an afternoon at Pirates of Parvati Freedom Café, which is perched slightly above the main trail and not beside the river as people sometimes assume. The view opened onto the trees, and the café offered tahini, fresh salad with lemon and olive oil, schnitzel with baked potatoes, and the usual pizzas, parathas, and garlic bread.

Here, the kitchens have a pace of their own - it is slow, languid, and they aren’t rushing you to get up and leave after finishing your meal either; you are invited to stay for as long as you like. In terms of the menu, they serve what people ask for because they’ve been asked for it a hundred times before.

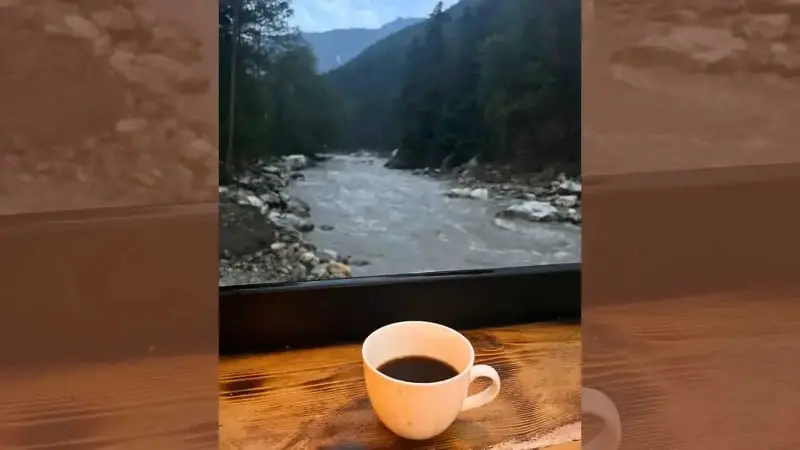

Katagla: Exceptional Coffee With Riverside Views

Katagla is often overlooked unless you know someone who’s already been, but once you cross into it, the atmosphere is different from Kasol or Chalal. It’s mostly Indian travellers who stop here to have a quiet getaway from the bustle, and what stands out the most is the line of cafés along the river. These cafés aren’t pushing one cuisine; they’re serving what works, and what works here are good desserts, proper coffee, thin-crust pizzas, and a mix of familiar plates with the occasional Israeli dish tucked into the corner of the menu.

While the focus isn’t heavily on Israeli food, I did see more people ordering things like falafel and hummus, usually alongside pasta or paratha. It’s not a full switch in style, but rather a soft inclusion, something that came with time as the cafés responded to returning guests who asked for certain meals. Places like ATS, House of Tales and White House have become comfortable in that in-between space, where the food doesn’t need to shout its identity, it just needs to taste good and suit whoever has come to stay.

Pulga: Café Culture That Grows Quietly Between Apple Orchards

Pulga, with its enormous majority of Israeli tourists, is a village that feels slower and more relaxed than the places below it, and that difference comes through in its cafés too. Prince Bistro is one of the more recognisable spots here, and it’s particularly known for its Israeli breakfasts, which usually include smooth hummus, soft flat pita bread, fresh salads, and sandwiches that are actually worth ordering more than once. The coffee here is strong, not overly sweet, and easily the best I had in Pulga. It’s a place where you’ll find people sitting through long afternoons with a book or headphones, not rushing through a meal.

A little further ahead, Devraj Café has a different feel. It’s more focused on full meals, breakfast platters, thaalis, and the kind of meals that work well after a trek or just a long day of walking around. The seating is straightforward and indoor, with a menu that doesn’t try to look global but still offers variety. The food is basic in the best way, cooked with balance, and served in generous portions that feel right for the pace of the village.

Tosh: Beneath the Snow Peaks, The Menus Still Speak The Same Language

Tosh, higher than Pulga and at the edge of where the road becomes a raw trail, still reflects the same food memory. Most cafés in Tosh are built with wide views and low benches, and the menus carry the same crossover: falafel, schnitzel, hummus, tahini, fried egg with salad, and masala tea all written together on wooden boards or chalk slates. The visitors were a mix, Indian, Israeli, and a few Europeans, and no one looked at the food with novelty.

It was here that I realised that Israeli food had stopped being “traveller food.” It had settled so firmly into the place that it no longer needed to be explained or named as foreign. You could eat sabich and siddu in the same meal, and it wouldn’t feel odd.

Also read: Shakshuka: A Breakfast Of Eggs Poached in Spiced Tomato Sauce

The Hippie Trail And The Food That Stayed Behind

The Hippie Trail, which once stretched from Europe to South Asia in the ‘60s and ‘70s, still exists in sections, especially in places like Kathmandu, Himachal, Rishikesh, Hampi, and Goa. Though its shape has evolved, its impact on food is clear. Travellers came and stayed in affordable hostels and guesthouses for extended periods, and what they craved began appearing in the kitchens. The menus grew slowly, shaped by habit and repetition, not marketing.

In Rishikesh, especially around Laxman Jhula and Tapovan, cafés now offer falafel, tahini salad, granola bowls, fresh fruit shakes, and lemon-ginger teas next to Indian dishes and Ayurvedic meals. The influence is soft but sustained, folded into the yoga school and ashram culture that draws long-staying international guests.

In the colder months, the backpacker crowd often migrates to Goa for a coastal retreat. In areas like Arambol, Mandrem, and Morjim, spaces have signs in Hebrew and Russian. They serve sabich, falafel, Russian Olivier salad, blini, babka, and Goan poi bread all under one roof. Here, Konkani cuisine exists alongside Israeli and Russian staples. It’s common to find a café offering lemon-mint smoothies, tahini, vindaloo, and pelmeni. The Russian influence is stronger in North Goa than in South, where vodka flows more than beer, and menus carry the Cyrillic alphabet. Regional drinks such as Fenni and Urrak are also welcome by tourists and locals alike.

And in Hampi, particularly in Virupapur Gaddi across the river, bamboo huts and cafés like Laughing Buddha and Gopi Guesthouse serve hummus platters, sabich, and sweet breads, but also ragi dosa and sambar. The menus blend easily, cooked by locals who have understood and mastered the cultural nuances of their visitors.

What’s common in all these places is that the food hasn’t been designed for effect. It’s there because people came and stayed and kept asking for what they missed from home. Over time, those requests became recipes that the cafés learned and repeated, until they became a part of the cultural fabric itself.

Summing Up

There’s something about the way Himachal absorbs people that makes this kind of cultural blend feel almost inevitable. You come here thinking you’ll find a quiet break from routine, but what you get instead is a place that’s been shaped by those who didn’t just pass through, but paused long enough to leave an influence. If anything, what’s happening here might only deepen. As more people come not just to see the mountains but to stay for a while, the boundaries between visitor and local soften.

What’s also clear across these towns is that the locals don’t resist these shifts. They aren’t rigid about how things must be done. For many of them, this is also their livelihood, and their instinct is to be good hosts: to accommodate what their guests need, including food that might not be from here. That openness is rarely one-sided. Most travellers, too, learn to engage with the local flavours and ways of living. The exchange feels mutual, not extractive. It’s a symbiotic relationship, and you notice it more the longer you stay.