Frank Tallis has 7,000 days left to live. “Roughly, if I’m lucky,” caveats the 67-year-old psychologist and author. But accepting that the end is in sight – and working out how to make the most of the time you have left – can all too often become a sticking point in our second chapter.

“Life after the halfway point has many challenges: loss of direction, physical decline, pain, redundancy, dissatisfaction, compromised authority, bereavement – and all endured in the long shadow of death,” Tallis explains in Wise: Finding Purpose, Meaning and Wisdom Beyond the Midpoint of Life. These have a serious impact on midlifers’ mental health – a third of over-65s experience significant anxiety and depression – yet “there is an enormous emphasis at the moment, and there has been for about maybe two or three years, on the young.” With Wise, Tallis says he “just wanted to redress the balance”.

Increased awareness of mortality, “fewer occupational opportunities, accumulated regrets and perceived irrelevance in a culture that overvalues youth”: it is these competing miseries that drive the midlife crisis, a term coined in the 1960s by Canadian psychoanalyst Elliott Jaques, and linked to insomnia and depression. It also afflicted the likes of Odysseus, Dante and Carl Jung.

In more recent decades, however, it has been recast as “a gift to comedy writers of the middle-aged man who confuses happiness with a motorbike and a younger partner”. But the male midlife crisis isn’t really a comedy, Tallis writes, “it is a tragedy”. This is borne out by statistics: a 2019 study of over 127,000 adults found that married men have better health than their single, divorced or widowed peers, while the longer the marriage, the greater a man’s chances of survival.

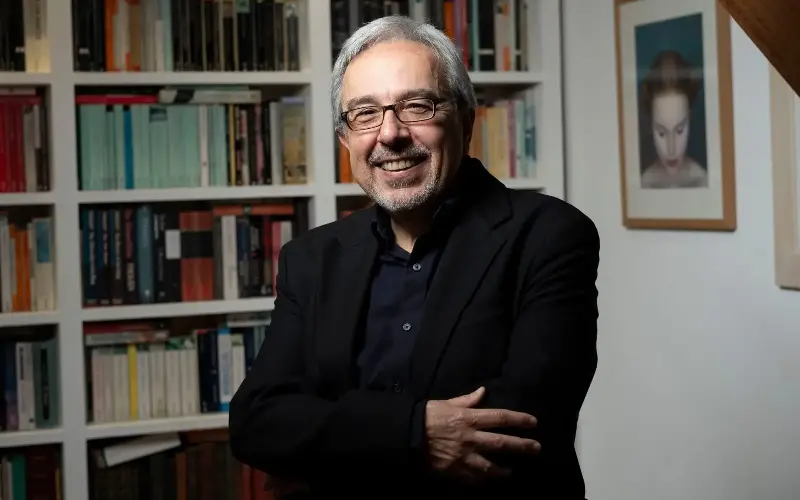

Even so, numerous clients came to Tallis’s couch with the belief that starting afresh in a new relationship would alleviate their midlife angst. “Our fantasies can be extremely attractive,” he says. “They have a lure. But if you subject them to very close scrutiny, you soon realise that, in reality, the alternative life will have all the same obstacles and problems,” he says from his book-lined study in north London. “Perhaps you can draw them closer to a prospective reality that isn’t so gilded.”

Those searching for a prescription for midlife self-betterment won’t find it in Wise, which weaves a philosophical path from the Stoics to Nobel prize-winners and contemporary neuroscientists, rather than offering practical self-help tips. “Everybody’s situation has its own peculiarities, so it’s very difficult to generalise meaningfully,” he says of his avoidance of specifics. Plus, “often you find clinically that you can tell somebody to do something, [but] it just won’t work.”

Tallis’s central thesis in the book is “achieving ‘wholeness’ – which could well be the essential condition for good mental health in later life.” He appreciates that the concept “sounds a bit vague”, explaining, “the idea of mind and body, the idea of conscious and unconscious, the idea of rationality and intuition; there are these polarities within the self that when fully integrated, when the self is more whole... results in lots and lots of benefits.” Essentially, the more self-aware you are, the better you can know yourself. This leads to better decision-making in all areas of life, and a greater sense of ease.

He points to standard self-help guidance for ageing: to eat well, exercise, socialise – all of which is good advice. “But of course, we already know it… people need to already be in a place where they can make use of that advice.” And so, when people ask how they might overcome midlife indignities, what they are in fact highlighting is an absence of wholeness, and “something that’s parked closer to, ‘how can I live wisely?’”

Does Tallis feel wise? “No!” he says with a laugh. “I do not consider myself to be a wise person; I have my flaws.” The book is no memoir, rather “a bit of public service” synthesising the views of great thinkers in a way he believes will be helpful to modern readers.

His own quest for wholeness stepped up a gear on his approach to his 40th birthday. That was when his self-professed “midlife crisis” – to become a novelist – kicked in. His wife was supportive, but many questioned why he would risk a well-established career – Tallis held a lecturing post at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience at King’s College London – for another that might go nowhere.

He was undeterred. “It was extremely good for me psychologically,” Tallis recalls of first writing fiction out of clinical hours, then dialling down his practice until he turned to full-time writing in 2008, when his second child was a toddler (he also has a child from his first marriage). “If I had not done that major act of integrating an aspect of myself into life that had previously been neglected, I think I would have some very profound regrets now at this stage in life.”

His punt paid off. He has written seven novels following the detective Max Liebermann, which have been turned into the BBC detective series Vienna Blood, while for the past decade, he has written mainstream psychology books on subjects from love (which Tallis calls a form of “sickness”) to lessons for modern life.

Swapping one lauded career for another seems a fairly mild case as midlife crises go. Had it not panned out, Tallis – who was born Francesco de Nato Napolitano to working class parents in north London, and didn’t begin reading books until he was in his early teens – could have joined writing groups. “I could have done things that satisfied that part of myself.” Some attempt at change “can still work out better” than changing nothing at all, he adds. “It doesn’t have to be a perfect, absolute solution.”

The problem is that too often, people wait for life-changing events such as a divorce or job loss before they take action – yet “things are happening all the time, but we’re not really registering them, because we don’t see them as being of a sufficient magnitude,” Tallis says. “People often postpone actual living, because they’re waiting for these big things to change them. Sadly, a lot of people find that life has gone by, and they’re still waiting.”

That can be compounded in midlife, where novelty has largely evaporated, and our senses begin giving up the ghost. Simply – and depressingly – “life gets duller as you get older. The lens of the eye yellows and retinal cells lose their sensitivity. A child’s summer is brighter than an adult’s summer.” Even the billionaires who used to come to his practice endured the same ennui (there are only so many pre-Raphaelite paintings one can jet around the world to). Pleasurable experiences lose their lustre: “orgasms, for example. Moreover, by late middle age, most people’s tastes and preferences are well-established and confined by limitations.”

The answer to overcoming this lands back at integrating the self, Tallis suggests, which is somewhat more challenging than consuming “quick fixes” online, where self help-fluencers tout often-baseless content in a bid for likes and shares. “When I was growing up, if you were easily influenced, that was an insult,” he says of today’s social media mores. Instead of pseudo life hacks, our focus should be on “knowing yourself, knowing your own mind, [and] not having to use an influencer or a celebrity to make you feel secure.”

Still, Tallis understands what it is like to be drawn in by self-ordained gurus. In his late teens, he ended up in a cult, which is “a little bit embarrassing now”, he admits, though in his defence, “it was the Seventies”. Lured by the promise of enlightenment – and having never been exposed to the Eastern philosophies this particular enigmatic leader espoused – he started attending spiritual gatherings at ashrams, and being encouraged to distance himself from family and friends. The pursuit of ultimate truth, as it turned out, involved a lot of financing the guru’s lavish lifestyle, and none of the transcendental bliss he had been promised. Several years down the line, he walked away. “But I found it extremely useful and instructive,” he reflects of that time. “It’s kind of protective with respect to other false gods and false gurus. You have, I think, a healthy scepticism.”

He was driven, as we all are, by a need to find meaning in existence. Now, he realises, “we are not obliged to find the meaning of life. If we can choose a way of being in the world that is personally meaningful, this will be sufficient to improve psychological health.”

How does he plan to make his remaining 7,000 days meaningful? Retirement, it seems, is out of the question. “Without appropriate stimulation, there is a tremendous risk, I think, of that shading into depression rather than the luxury of infinite time and opportunity.”

And so Tallis is writing his next book, about the relationship between the mind and technology, though he likes the idea that he might “spend more time doing nothing, which of course isn’t really doing nothing” – rather the opportunity to be reflective, and allow self-observation through stillness. “I have a notion of things that I want to continue doing,” he mulls. “But remaining useful and connected both feature quite significantly.”

Wise: Finding Purpose, Meaning and Wisdom Beyond the Midpoint of Life by Frank Tallis is published by Abacus

Tallis’s tips for living well into midlife and beyond

Tap into your daydreams

“Daydreaming is probably more important to healthy ageing than is generally appreciated,” according to Tallis, with daydreamers found to have thicker cerebral cortices (the cortex thinning has been associated with cognitive decline in older people). While daydreams are often dismissed as the brain “idling”, they can be associated with creativity, problem-solving and self-reflection.

Prioritise social quality, not quantity

Accepted wisdom is that as we age, our social lives become increasingly important. But studies of well-adjusted older people by Swedish sociologist Lars Tornstam showed that “a single meaningful connection can be more powerfully transformative than having a room full of associates. The quality of the conversation in terms of psychological health is very important.”

Don’t shy away from death

“None of us really believes in our own death. It is extremely difficult for brains to conceptualise nothingness,” which is “terrifying in terms of its incomprehensibility.” Tallis says we may find solace in guidance from the Stoics, who advised considering death in the same way as life before birth. “Most people aren’t particularly fearful, or concerned, or troubled by the idea of their non-existence before birth, and they suggest thinking of death as being just more of the same.”

Watch what you say to loved ones when you argue

“You will say things to the person who you are supposed to love, the person you are closest to, that you wouldn’t actually say to anybody else. These can be injudicious, all the way to cruel.” Tallis advises looking at this behaviour not merely as “I just behaved badly”, but as a window into our subconscious.

Think of the bigger picture

Being more connected to nature, the world and other people is key to wholeness, Tallis says. “A very good indicator of mental health and old age is a transpersonal view (thinking about things beyond the merely personal) – like being concerned about climate change – “even though the person would very likely be dead before the worst happens.”